The Biggest Tragedy of the Italian Community

SS ARANDORA STAR

THE HISTORY

It was in the early hours of 2 July 1940 that the SS Arandora Star – a British passenger ship requisitioned for military duties at the start of the 1939 conflict – sailing unescorted from Liverpool to St John’s, Newfoundland, was intercepted and torpedoed by a German U-47 submarine patrolling the Atlantic waters, 75 miles off the Irish coast of Donegal.

In excess of 1,500 people, Italian civilian internees, German prisoners of war, and Jewish refugees were on board. Painted battleship grey, the SS Arandora Star had not been marked as a prisoner of war ship, the railing of the decks had been heavily layered with barbed wire to prevent any attempt to escape, the lifeboats available were insufficient for the number of people embarked.

When a German torpedo struck its target there followed first panic, then mayhem. Sergeant Norman Price, one of the British military guards, later recalled:

“I could see hundreds of men clinging to the ship. They were like ants and then the ship went up at one end and slid rapidly down, taking the men with her… many men had broken their necks jumping or diving into the water. Others injured themselves by landing on drifting wreckage and floating debris near the sinking ship.“

The SS Arandora Star sank in just over 30 minutes taking with her more than 800 men to their death. Over the months that followed, bodies washed up on Irish shores and the Hebridean islands. Often unidentified, they were given a Christian burial, but only a few victims have a marked resting place.

The 712 Italian civilians on board had been ‘rounded up’ and held captive not for any other reason than their just being ‘Italian’, enemy aliens considered a ‘Fifth Column’ and, by assumption, a menace to national security. Four hundred and forty-six of them perished, one of whom was Decio Anzani, a long-standing opponent of the Fascist regime and friend of George Orwell and Sylvia Pankhurst. Winston Churchill’s policy of ‘collar the lot’, was the panic response to the threat of a military invasion.

May they rest in eternal peace

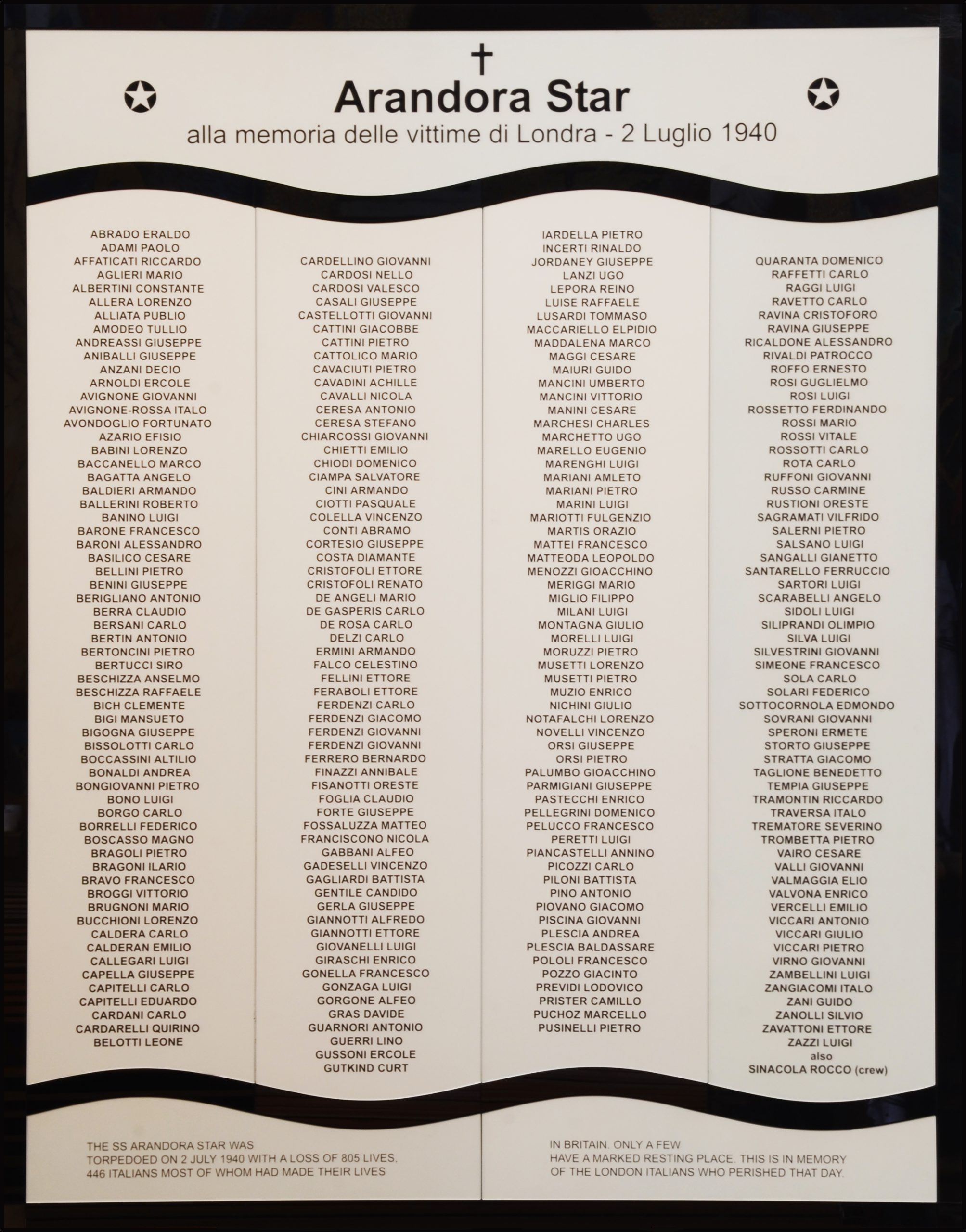

THE LONDON ITALIANS WHO DIED

The original Arandora Star London memorial (below). And further below, the Mazzini-Garibaldi Club led the campaign for the London memorial to victims of the Arandora Star tragedy.

The memorial, which commemorates 241 named London Italians who died aboard the ship, was unveiled in St Peter’s Italian Church, Clerkenwell, London, on 2 July 2012, the 72nd anniversary of the tragedy.

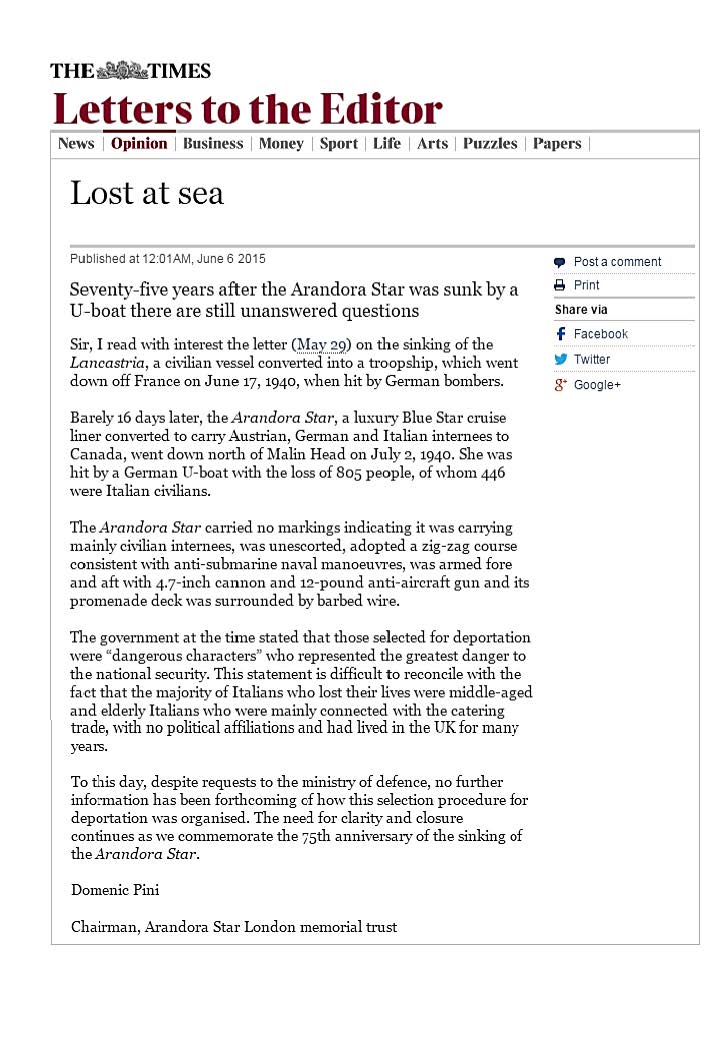

2 July 2015

75TH ANNIVERSARY

On the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the sinking of the ship in 2015, the Arandora Star London Memorial Trust and the London Italian community organised a number of commemorative events, including:

- Publication of a Commemorative Book called The Arandora Star Tragedy – 75 Years On, London’s Italian Community Remembers.

- Presentation of the Commemorative Book at London’s Italian Cultural Institute.

- A touring exhibition, which began at Holborn Library from July to October 2015.

- Mass at St Peter’s Italian Church, Clerkenwell Road, London EC1 on the evening of the anniversary with Sir Keir Starmer making a speech.

Exhibition Photos

Exhibition Boards for the 75th anniversary.

Bardi Exhibition Photos

The Exhibition presented in Bardi, Italy.

Permanent Display

The Exhibition at the Italian Consulate

Remnants of a lifeboat from the SS Arandora Star

Remnants of a lifeboat from the SS Arandora Star

Remnants of a lifeboat from the SS Arandora Star

SS Arandora Star - Derby Cup

Peter Capella addressing the audience

Caterina Soffici and Dr Massimiliano Mazzanti

Dr Massimiliano Mazzanti, Italian Consul General and Peter Capella

From left to right: Victor Menozzi, Peter Capella, Roberto Stasi, Domenic Pini, Massimiliano Mazzanti and Caterina Sofici

Domenic Pini's article in La Notizia.

Remnants of SS Arandora Star at the Italian Consulate

Maria Serena Balestracci’s

ARANDORA STAR

Dall’oblio alla memoria. From Oblivion to Memory (bi-lingual)

2nd July 1940, 6.58am: the British liner Arandora Star is sunk by a German submarine in the Atlantic Ocean.

A tiny chapel in a village cemetery in the Parma Apennines commemorates the victims of the disaster, including 446 Italian civilians who had settled many years before the war in Great Britain and were being deported to Canada on the ship.

Why was such a tragedy allowed to happen, and why is the story so little known in Italy? This book is an attempt to answer these questions, approaching the story from two different but linked points of view: the history of the events of 1940, complemented by the accounts of survivors and of the victims’ families, together with previously unpublished photographs of the rescue operations; and the personal perspective of the author, a sort of diary describing the many meetings, journeys, coincidences and small but vitally important events thanks to which it became possible to ‘rediscover’ the tragic story of the Arandora Star.

Olive Besagni’s

A BETTER LIFE

A history of London’s Italian immigrant families in Clerkenwell’s Little Italy in the 19th and 20th Centuries.

This collection of almost 40 oral histories tells the stories of Italian families who emigrated to the slums of Clerkenwell, London, from the early 19th century onwards, in search of a better life than in the poverty-stricken rural hamlets of Northern, and later Southern Italy.

It vividly describes their courage in the face of hardship, their childhood preoccupations and family loyalties, their teachers and mentors, the trades and careers in which they endeavoured to gain a livelihood, their marriages within and without the community and the Catholic faith, the devastating effects of two world wars on these families, their sicknesses, tragedies and triumphs. All illustrated by precious family photographs.

Olive Besagni is a long-time member of the Mazzini-Garibaldi Club. She collected these stories while she had a column called “The Hill” on “Backhill”, at that time a paper publication run by St. Peter’s church. For five years, she published every week the story of a family. Many people contacted her providing also old photos of their relatives and their childhood.